To celebrate the arrival of 2025, I decided to compile a series of Apple’s top ten major areas of innovation occurring over the past 25 years. Some of these revolutions are overlooked when looking back at the company’s dramatic turnaround and decades of introducing world-changing products.

Following the Year 2000 release of Mac OS X Public Beta and its legacy of updates up to and including today’s macOS 15 Sequoia (and its successor to arrive later this year), here’s a look at Apple’s second major initiative of innovation, both in the sequence of time and in relative importance across the last quarter century, and what it means for Apple today.

This second facet is Apple’s unfolding strategies in selling the technology it had assembled into products and services to its customers. It’s been an unparalleled accomplishment of the company over the past 25 years, and an integral element in Apple’s incredible success as a global innovator. Further, it’s actually resulted in making Apple’s products better.

This series isn’t merely refuting the obviously non-serious and absurdly simpleton idea that Apple somehow isn’t really the world’s leading innovator in personal computing. It’s intended to offer a some insights from the past 25 years to illustrate how Apple has incrementally built out strategies to support its future growth and development.

The first of these — the radical rearchitecting of the original Mac OS with what was at the time branded as Mac OS X — laid the foundation for vast new leaps in product technology far beyond Apple’s then-existing portfolio of desktop and notebook Macs. The products that followed would not have been possible if Apple had attempted to merely continue adding minor refinements to its aging, original Mac platform.

The absurdist meme that Apple Can’t Innovate

Criticism that Apple “couldn’t innovate” certainly surged after the death of Steve Jobs in 2011. After his death, Jobs was held up as an iconic thought leader with a remarkable talent for identifying critically important strategies that resulted in blockbuster, world-changing products and services.

There was widespread concern after Jobs’ passing that Apple would lose its creative spark and devolve into being just another mindless, middling corporation struggling to bring bland ideas to fruition. In fact, it was popular to suggest that Jobs’ hand-picked successor, Tim Cook, was not the visionary that Apple desperately needed but merely an operations guy who couldn’t see the big picture.

Global operations leaders literally see the big picture; that is the very job they are tasked with.

Over the last decade and a half, Apple under Cook has demonstrated an incredibly prescient ability to once again completely reinvent the Macintosh while keeping iPhones and iPads at the pinnacle of global innovation. Cooks’ Apple has also launched a series of radically innovative new product categories and technologies.

Some of these arrived without anyone even imagining they should, including AirPods, AirTags, privacy-retaining Covid-19 reporting tools and the automatic handling of SMS one-time-code authorizations in two-factor authentication.

Well this didn’t age well

Well this didn’t age well

Certainly, one of Jobs’ most profound legacies was implanting the dynamic culture of Apple itself, which has flourished under Cook. Jobs infused the company with a corporate culture of competence and most certainly creative innovation. Jobs’ Apple was stridently focused on delighting users with something “insanely great,” rather than just aiming deliver “carrier friendly, good enough,” as Samsung phrased its own ambitions internally.

Across the last 25 years, it hasn’t been Apple that’s intending its new products and services to first and foremost suit the needs and desires of surveillance advertisers, rather than the actual humans buying them. It’s impossible to say that about Google, Facebook, or other Android licensees and smart TV manufacturers.

The most notable aspect of relentless innovation is refusing to remain comfortably stuck in the past, or resisting any efforts to keep moving boldly into the future. In acknowledgment of that, Apple’s headquarters prominently displayed Jobs’ famous quote:

“I think if you do something and it turns out pretty good, then you should go do something else wonderful, not dwell on it for too long. Just figure out what’s next.”

Notably, that quote came from an interview conducted in 1995— well before Jobs returned to Apple and began dramatically turning the company’s fortunes around.

It’s also important to remember that criticism of Apple’s “ability to innovate” didn’t originate with the passing of Jobs. Even well before Jobs returned to lead Apple starting in 1997, he was disregarded as having lost out to Microsoft by prominent Windows writers.

After his return to Apple, his every move was castigated, denigrated and scoffed at by PC industry figures. They scoffed at the “lame” iPod. They even famously giggled at iPhone— where was its little Blackberry keys?

Microsoft’s CEO Steve Ballmer famously mocked iPhone at its arrival as “most expensive phone in the world” while insisting that “there’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance!”

In 2016, Apple was supposed to fail like Blackberry had

In 2016, Apple was supposed to fail like Blackberry had

Even after Jobs’ iPhone kicked their collective asses to the curb, they again laughed at and disparaged iPad three years later.

Barely three years after that, tech enthusiasts were abuzz about Apple being the “next Blackberry,” because they were convinced Google was going to rush in and bring Voice First AI assistants to smartphones while an unprepared Apple dried up and blew away.

That was in 2016, nearly ten years of tech eternity ago. Absolute disbelief in Apple’s ability to innovate its way into new markets was so over-the-top dramatic that a 2023 movie was made about Blackberry and its rapid fall into irrelevance at the introduction of Apple’s iPhone.

Perhaps in a few years they’ll make a dramatic movie about Google’s cocksure arrogance about the supremacy of Android and how its confident army of PC and electronics licensees were summarily sidelined into obscurity just like Blackberry was.

Is an Apple by any other name just as sweet?

Long ago, prominent PC users had similarly scoffed at the 1984 Mac’s mouse and graphical windows— before belatedly adopting the ideas enthusiastically after they were reheated and fed to DOS users by Microsoft’s Windows 95.

They again scoffed at Mac OS X’s candy colored, translucent windows in 2000, ridiculed Apple’s radically “light and thin” approach to portable computing introduced by Jobs’ 2008 MacBook Air, and dismissed Apple’s longstanding efforts to move beyond Intel’s “industry standard” x86 architecture and boldly shift personal computing to purpose designed, ultra efficient, and radically novel new SoC architecture with ARM silicon and integrated graphics.

I shouldn’t have to remind you that Windows Vista was designed to look and feel just like the Mac OS X it followed six years later, or that every PC laptop today desperately looks and feels as much like a MacBook Air as is possible, or that Microsoft, its PC makers and its chip partners are all scrambling to look and feel like they are in the same decade as Apple Silicon Macs.

But now, keeping in mind all the negativity Apple faced as a product innovator trying to sell its new technologies, let’s take a look at a second major facet of Apple’s innovation over the last quarter century: how it managed to sell them.

2: The revolution of retail with Apple Store in 2001

Apple’s second major revolution of the 2000’s wasn’t a hardware or software product. It was instead a way to get Apple’s products in front of buyers. It was challenged with how to demonstrate their uniqueness and how to develop a personal relationship with customers that could make them comfortable with trying new things, confident that they weren’t just experiments in a privacy-compromising effort to sell ads.

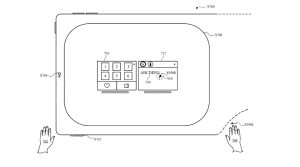

Just over a year ago, I noted that “the initial work of launching its own Apple Stores was initiated in 1997 by Steve Jobs as one of the first problems that needed to be fixed at the then-struggling Apple Computer. At the time, Macs were sitting disheveled in department stores or in a corner store within a store’ inside CompUSA discounters.”

Apple’s customers who can remember back to the late 90s can tell you all about how pathetic Apple’s direct sales channels were. Department stores such as Sears and Wal Mart contractually put boxes of Macs next to PCs. Their sales associates recommended Windows alternatives. In fact, retailers were increasingly incentivized to promote their own store brand of generic Windows PCs, which delivered the highest profit margins to the retailer.

Macs at Sears

Macs at Sears

“Store-within-a-store” efforts initially attempted to differentiate and showcase Apple’s products more attractively. Many technology and electronics companies today continue to follow this strategy inside of big box retailers. Yet few go beyond this to create their own retail stores. In part, it’s because retail is extremely difficult and expensive to achieve.

Even companies that have slavishly copied the look and feel of the Apple Store, down to the shape and color of its tables— notably Microsoft, Samsung, to some extent Google, and of course all of the copycat Chinese phone makers— have struggled to actually achieve anything similar in terms of results.

That’s because the Apple Store required a deep level of innovation to develop, implement and maintain. Nobody in technology is innovating on the level of Apple in retail. This has held true over the last 25 years following the opening of its first retail stores in 2001. But the Apple Store wasn’t the company’s first solo effort at direct retail sales.

Web, Objects

Job’s first steps toward fixing Apple’s broken direct sales for Macs occurred immediately after the acquisition of NeXT (which was announced in the final days of 1996). Well before it could throw open new retail outlets, and even long before Apple could adapt NeXT’s operating system to serve as the foundation for Mac OS X, Apple began making use of the object oriented web development middleware NeXT had been marketing as WebObjects to deliver a powerful new direct sales website for retailing Macs by itself.

WebObjects was essentially NeXT’s application development tools, hosted by a Java web server rather than a Unix kernel. NeXT had initially launched in 1988 as a complete computer system— effectively the “next Macintosh.” Yet its failure to find sustainable markets for its advanced systems prompted Jobs’ company to abruptly shift away from selling its Mac/PC competitor workstation hardware.

NeXT first tried licensing its complete NeXTSTEP OS as an alternative to Windows for PCs, and then pursued efforts to sell its advanced application development environment as software that could run on top of Windows, or as an environment hosted by Sun’s Solaris, or UNIX workstations from IBM and HP. As all of these hopes incrementally failed to commercially materialize, NeXT decided to move to the web and Java, using its development tools as a way to rapidly build rich web applications that could easily integrate with a backend relational database.

WebObjects was initially picked up by PC maker Dell, which used it to build one of the first sophisticated online web stores for direct PC sales. Microsoft was outraged. After Apple acquired NeXT, Dell rapidly scuttled its WebObjects store and reimplemented it using rival web development tools from Microsoft.

Dell’s early success with WebObjects made it easy for Apple to see what to do with the new software it now owned. It managed to open the doors of its own new online store for Macs within 1997, just weeks after the acquisition closed.

Apple’s online store in 1997

Apple’s online store in 1997

Implementing a new online store using NeXT’s WebObjects technology was not only much easier than adapting the NeXTSTEP operating system to run on Macs (which didn’t initially happen until Mac OS X Public Beta in 2000), but was also easier than completing Apple’s internal “net PC” concept, which would take another year to arrive in the form of the New iMac in late 1998.

Yet once iMac arrived, Apple already had a working direct online sales channel in place to help buyers order it, thanks to the WebObjects-powered online Apple Store. That helped make it obvious that Apple not only needed to build new products, but to also build effective ways to sell those directly to consumers.

Not the first on the block

Apple’s goal of building out its own physical retail stores wasn’t an original concept that nobody had ever thought about doing. Gateway 2000, a generic PC maker, had already built out a series of retail stores to market its cow-themed computers, just as mobile phone carriers had quickly rolled out retail storefronts to offer increasingly ubiquitous cellular phones.

Sony, which in 1999 was living the dream as the Apple of its day, had embarked on a concept of building “urban entertainment centers,” notably including San Francisco’s Metreon, as well as retail flagships in Tokyo and in Berlin’s glitzy new Potsdamer Platz complex then named Sony Center.

One of the Sony Metreon’s key tenants beyond Sony itself was Microsoft. It hoped to excite technology enthusiasts with its Windows PCs and the ill fated WebTV Network for browsing on your television. Microsoft gave up and shuttered that early experiment in retail by 2001.

Microsoft first retail store had a shorter lifespan than a Zune

Microsoft first retail store had a shorter lifespan than a Zune

Today, twenty five years later, few people could tell you anything about Gateway 2000. Sony’s shingle has been stripped from the Metreon and the former Sony Center in Berlin. It has delegated its hardware sales to authorized retailers.

Microsoft not only gave up on retail initially back in 2001, but also tried again valiantly a second time to copy Apple Retail in 2009, and failed even more spectacularly. It effectively built an expensive chain of perpetually empty locations.

Those stores did absolutely nothing to save Microsoft’s parallel efforts to copy iPhone and iPad with its own Windows Phone, Surface and other big budget, high effort failures. Microsoft threw in the towel on retail in 2020. It converted its four most expensive flagship locations into “Microsoft Experience Center” museums.

Imagine being aware of all of this reality and still wanting to believe that Apple is a failure at innovation.

First Movers are often first losers

A lot of people are also completely convinced that being a “first mover” implies inherently having a clear and insurmountable advantage, and that rushing “something” to market is both essentially important and also evidence of your virtually guaranteed success.

We recently have read a lot about this in the context of artificial intelligence. Many tech media writers highlighted a desperately important “first mover” advantage seized by Samsung and Google in claiming that their phones “had AI” last year, long before AI on a mobile phone has proven to be a notable advantage. As noted above, that message was just a recycled version of what was being said back in 2016!

Just a few years ago there was non-stop clamor about 5G, and how having 5G would turn the tables on mobile sales and finally stop Apple from inhaling the majority of mobile phone profits, because some Android phones “had 5G” first.

Over the last 25 years, there’s been a gushing firehose of “first mover advantage” tales regarding Apple falling behind in everything from fingerprint scanners to waterproof phones to phones that fold out into Android tablets, or televisions that are “soft-of” also PCs, or PCs that are “sort of” also tablets— yet all of this confidently announced contrivance has amounted to nothing.

Anything really novel and useful that Apple’s competitors have brought to market “first” has been matched and often surpassed by Apple itself. Touch ID and waterproofing, not to mention 5G and AI, are all better on iPhone than elsewhere. Pundits nearly ran out of breath professing their insistent adoration of convergence TVs and folding phones and hinged notebooks with nobody really caring in the end.

On the other hand, Apple has significant product advantages with features that have not been successfully copied, ranging from good trackpads to well implemented resolution independence. But this article is about retail, so let’s take a quick look at how much Apple has innovated in a category no one else can even effectively copy, even with unlimited billions of dollars.

What’s innovative about the Apple Store?

The Apple Store, since its initial introduction in 2001, is particularly notable for its revolutionary approach to retail. Rather than just serving as a retail outlet to sell products, it has been designed— like other Apple products— to deliver an experience.

Steve Jobs opens the first Apple Store in 2001

Steve Jobs opens the first Apple Store in 2001

Apple designed its retail stores to be immersive brand experiences, not just conventional stores. Their layout and aesthetics are intentionally designed to reflect the simplicity and elegance visible across Apple’s brand.

Unlike traditional stores— and in marked contrast to the dowdy department stores tasked with selling Macs 25 years ago— Apple Stores invite customers to touch, use and really experience products. Their open, minimalist design allows people to engage with Macs, iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch and now Vision Pro without commissioned salespeople hovering over them. Apple’s self-service model of interaction encourages curiosity and a deeper connection with its products.

Yet Apple Stores aren’t just minimal and basic; they are notable for their unique architectural designs, which are both sleek and functional and also creative and dramatic— often spectacularly.

Most feature expansive glass windows, large open spaces with trees, cathedral high ceilings, and standout features ranging from bombastic glass stairways, to innovative reuses of grandly historical buildings. They use ultramodern materials that reflect the company’s focus on design and aesthetics across all its products.

Apple Stores also regularly make use of precision crafted, state of the art materials ranging from large format, cleanly transparent architectural glass to natural stone and wood tables and shelves that draw a warm halo over its products, associating them with its expensive, desirable, high value environment.

Apple Stores have also increasingly hosted a “town center” concept as a communal gathering place for buyers to not just shop, but to take part in free educational sessions, creative workshops and tech tutorials, strengthening the brand’s role as not just a product seller but also an enabler of creativity.

“Today at Apple” is often held in front of a technologically impressive huge video display, presenting workshops and events on topics from music to photography and programming.

Apple has even made it possible for users to ring up their own purchases using an iPhone app— effectively a curated experience with the self-directed appeal first delivered by the WebObjects-powered Apple Online Store for building custom “made to order’ Macs a quarter century ago. The company has also added services like contactless delivery and curbside pickup to facilitate flexible transactions.

One of the original features of the Apple Store was its Genius Bar, a tech support area where customers can get help with their devices. This innovative service reinforced the Apple culture of customer-centric care and created a direct, personal relationship with users. It also made buyers feel more comfortable with their purchases, and thus gave them the security to confidently invest more when making purchases.

Buyers could feel confident in knowing that they wouldn’t be quickly stranded with a complicated but unsupported device or service canceled at the whim of Google, or update-abandoned by an Android licensee.

University Village Apple Store, Seattle

University Village Apple Store, Seattle

Just as importantly, the Apple Store’s role in servicing Apple products has given the company deep insight in the problems users can experience. This feedback loop has greatly enriched the design cycle of its new releases, resulting in better products.

I USB-C what you did there

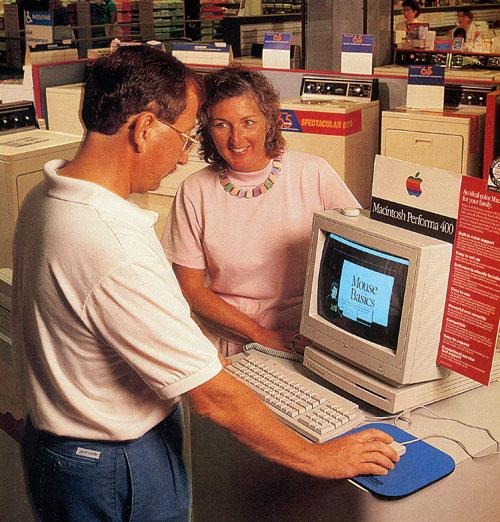

One example: before 2012, Apple’s mobile devices used the “30 pin dock connector” to charge and sync. This substantial cable and port was both strong and delicate: any damage could render the whole product unusable, resulting in a very expensive repair or outright replacement.

Starting with iPhone 5 in 2012, Apple introduced Lightning, which upgraded the mobile connector in many ways. It was faster, smaller, more powerful and featured a bidirectional fit that attached in either way you might try to plug it in.

Lightning was a technological leap designed to solve users’ problems

Lightning was a technological leap designed to solve users’ problems

Apple patented Lightning’s innovations, including its dual orientation connector, “having a connector tab with first and second major opposing sides and a plurality of electrical contacts carried by the connector tab.”

Apple hoped to license the Lightning connector, which included an authentication chip that was smart enough to recognize how it was plugged in and to adapt to either direction. Most of the PC industry decided to instead stick with the less sophisticated variants of existing USB plugs.

Some customers complained that Lightning cables’ relatively weak wiring design frequently resulted in broken, unusable cables.

This was by design.

Apple had direct insight into how its products were used and what caused common repairs, and the severity of those repairs. In making Lightning the weak link of a brutalized junction, Apple enabled buyers to manage the damage of their own manhandling with the purchase of another relatively cheap Lightning cable, rather than a new phone or a very expensive repair.

Android phones of the era typically used mini-USB and then micro-USB. Like Intel’s tragic original design of USB 1.0 connectors, these rudimentary and cheap plugs needed to be inserted in one specific direction, requiring that users typically had to try shoving it in three times before getting it into the port. Even worse, the crudely basic, bent-metal USB connectors resulted in strong enough leverage to ensure that too much stress on your cable would inevitably result in damage to the port or logic board on the device.

The disposable nature of these Android phones accelerated their need to be thrown away and replaced, inflating Android’s overall sales numbers. Android users may never have noticed how badly their phones survived physically, because Androids rarely got more than a few months of OS and security updates anyway. Makers certainly didn’t care that they were selling lots of replacement devices.

Apple’s superior design of iPhones, including their abuse-resilient Lightning ports— as well as the company’s years-long cycles of free iOS support— resulted in most iPhones having extraordinarily extended second lives as family hand-me-downs and fueled a vibrant second hand market for used iPhones.

This helped make the “most expensive phone in the world” much more affordable. It allowed tech hungry enthusiasts to excitedly buy every new model knowing that they could still sell their old one for a still significant sum. It also allowed people with limited funds to get previously-owned iPhones at prices competitive with the cheapest Androids. It took pundits and market researchers many years to figure any of this out.

This cycle would have fallen apart if Apple hadn’t relentlessly updated its new products every year. That cycle of innovation was also driven by the treasure troves of real world user and repair data Apple Stores made available. Google and its Android licensees didn’t have similar data available to them. There largely wasn’t any mobile user data for Microsoft to even try to collect.

Today’s Androids were “first” to arrive at implementing USB-C. That upgrade from mini-USB must have felt like a spectacular leap, but many of its features were already delivered to iPhones a decade earlier in the form of Lightning. In fact, it was Apple’s participation in the USB consortium that fueled USB-C’s big leap in physical design over its previous generations.

USB’s legacy ports were originally created by the consortium’s founding PC makers (which included Microsoft) primarily to be cost effectively cheap. USB ports evolved only in incremental baby steps for an agonizingly long time until Apple joined the consortium and demonstrated how to build a rugged, intuitive port. USB-C is really close to being the female version of Lightning, with additional conductors that can support faster bandwidth and modern device charging protocols.

Apple’s shared technology benefitted everyone. Apple itself first implemented USB-C with the release of the 2015 Retina MacBook in 2015, just 3 years after the debut of Lightning. Beyond USB’s own serial bus protocol, the USB-C physical connector is also used for DisplayPort and Thunderbolt 3, 4 and 5 which can serve as the connectivity of a PCI-E slot, over a cable.

Modern Thunderbolt uses USB-C

Modern Thunderbolt uses USB-C

The shift from Lightning to USB-C on Apple’s mobile devices and peripherals was less compelling and urgent. USB-C’s main advantage over Lightning is its much faster ability to host USB 3.0 and other higher speed protocols, which weren’t really yet relevant to iPhones or keyboards or remotes. Lightning also had a massive installed base of surviving cables among users, which would need to be incrementally replaced.

By decisively slow-walking USB-C from Macs to iPad and most recently to iPhones, Apple users have had time to adjust and accumulate USB-C ports and cables before Apple flipped the switch on tens of millions of new iPhones. Efforts by EU bureaucrats to legislate how technology should work by fiat were as unnecessary and ignorant as their previous attempts to force everyone to use micro-USB. We can be thankful that they failed.

Modularity vs Integration

Another learning experience facilitated by Apple Store data pertains to the ease of self-repair by end users. Having long ago worked in an Apple repair shop, I frequently wondered why Macs weren’t designed to make it easier for users to swap out failed parts on their own. In fact, there is an entire cottage industry and political movement dedicated to the concept and rights of end users and self-repair.

Back in the days of the early iPods, Apple was selling whimsically designed Macs ranging from the Cube to the igloo iMac. These were notorious difficult to service. As it shifted toward the modern design of iMac (effectively being a computer on the back of a flat screen), user serviceability changed dramatically.

By the time the first Intel iMacs arrived in 2006, the all-in-one’s modular design was almost comically easy to pull apart. It was intentionally designed to facilitate the ease of replacement components, even by end users, who could pull and ship some defective parts directly to Apple for a replacement.

However, just as with cars before the 1990s, these easy repairs required mechanisms for unlatching and detaching components, requiring larger, bulkier overall dimensions. Additionally, as anyone who’s serviced a defective car knows, it can get extraordinarily expensive to just randomly begin replacing parts until the problem is fixed. Without an expert understanding of proper, thoughtful troubleshooting, a part-replacement mechanic is likely to generate massive expenses, perhaps without even fixing the issue.

If it’s effortless and easy to pull off the display and send it in for replacement, that expensive part swap-out is likely to happen, That’s true even if it does nothing to resolve, say, an issue caused by a loose connection of the wiring harness driving the display. The very fact that the display has the weak link of a pullable-plug connector with the potential to cause the problem comes from the reality that it was designed to be so modular in the first place.

Expensive Apple Store repairs of millions of devices not only informed the design of Lightning, but also ended any interest at Apple at making computers and devices that were as modular as a Boomers’ Lincoln Continental.

Informed by the reality of repair data, Apple quickly shifted away from the easily detachable modularity of devices, right around the same time it delivered Lightning. The 2012 iMacs began to ditch magnetically attached screens, standard screws and other modularity features and instead began the introduction of adhesive construction within lighter, thinner unibody designs.

Apple Store experience helped iMac evolve into a radically thinner, lighter product, rather than a big modular toolbox

Apple Store experience helped iMac evolve into a radically thinner, lighter product, rather than a big modular toolbox

Critics who already were already sick and tired of screaming about replaceable phone batteries from the Nokia-era now bewailed the erasure of Chevy-like wiring harnesses and standard PC hard drives that bolted into a cage like a modular car radio deck on your fathers’s Oldsmobile.

Yet the products Apple makes rapidly got easier to carry, radically thinner, stronger and more rigid. They managed heat better, requiring fewer fans and operating quieter. They were less upgradable, but you knew that when you bought it so you gave more thought to your actual needs at the time of purchase.

Repair costs plummeted and the time involved with waiting for part swaps rapidly decreased. The decline of modularity came hand in hand with solid state components (with radically fewer moving parts) and the shift from optical media to networking and cloud storage. But boldly erasing modularity was a key factor that enabled Apple to deliver better, more reliable products with fewer points of failure.

This might seem obvious in hindsight, but other makers who didn’t have Apple Store repair data famously tried the opposite approach. Many Android licensees bent over backward for years to placate their most histrionic customers with modularity pipe dreams, including those ridiculous replaceable batteries that have all since mysteriously vanished.

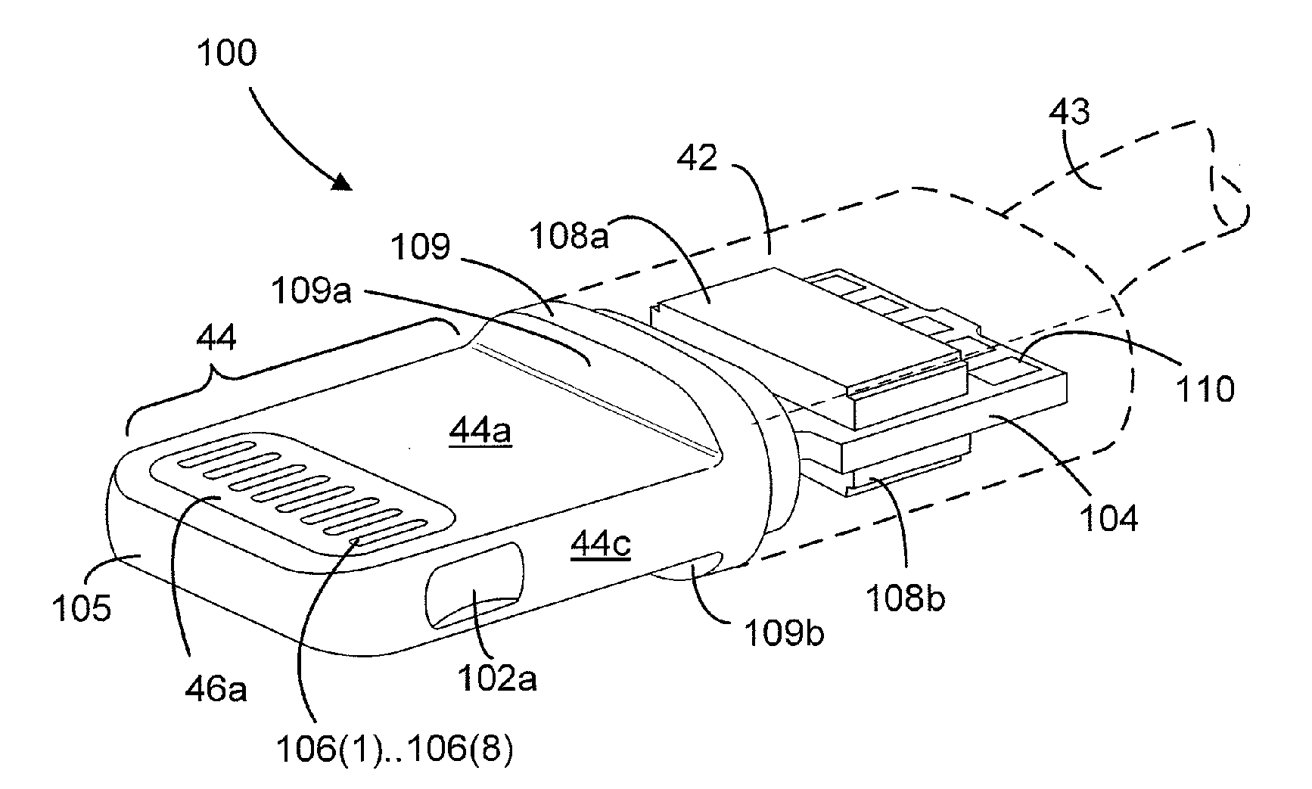

Well after Apple began moving away from modularity, Google quite seriously sponsored Project Ara, with the supposed intent of creating a smartphone with components that could be swapped out like Legos.

Well this didn’t age well

Well this didn’t age well

Google inherited work on the idea of smartphone modularity from Motorola when it purchased that company for a breathtaking $12.5 billion in 2011, with the expectation of using it to build its own Android phone. Google did indeed release a Motorola-branded phone (known as Moto X) with some marginal cosmetic modularity “features,” but it only achieved a humiliating level of spectacular failure, and it ended up completely destroying an American technology icon in the process.

Yet even after Google sold Motorola’s remains to China in 2014, it purposely retained control over Project Ara and continued internal work on the holy grail of modular mobile devices, accompanied by strident public outreach that castigated Apple for daring to upset the Android faithful by taking away their Lego dreams.

In 2016, Wired took the lead in evangelizing Ara with the vacant but urgent credulity of a doomsday cult with its KoolAid-day scheduled for tomorrow.

Four months later Google completely abandoned Ara. It returned to the drawing board and came back to market with something that was even more like iPhone than ever before: the modularity-free Google Pixel.

![]() Google’s “Pure Android” Pixel XL was priced the same as Apple’s iPhone 7 Plus but was half as fast, lacked Optical Image Stabilization, a telephoto lens, weather resistance, support for wide color gamut and stereo speakers

Google’s “Pure Android” Pixel XL was priced the same as Apple’s iPhone 7 Plus but was half as fast, lacked Optical Image Stabilization, a telephoto lens, weather resistance, support for wide color gamut and stereo speakers

A new way to sell technology

Apple Retail not only informed the development of new Apple products, but also originated an entirely new model for selling technology.

Before it, PCs and electronics were largely marketed through price competition, where regular seasonal sales and advertised discounts, along with free bundled accessories, were emphasized along with bullet points of must-have features. This is the most simplistic and ordinary way to move products, and is ubiquitous among tech marketers and big box retailers.

In contrast, Apple Stores focus on the experience of using Apple products, educating consumers on the benefits of product features rather than just overwhelming them with check marked feature lists.

Apple’s products almost never go “on sale,” encouraging buyers to get what they want when they want it, rather than waiting for the inevitable discount. Buying a product right before it goes on clearance is frustrating. Buying a product that is consistently priced is inviting.

Apple Retail was so unusual and different from existing retail operations that media wonks initially speculated that Apple would fail. Instead, its stores were extremely successful, bypassing the sales numbers of competing nearby retail. Within three years, Apple Retail reached US$1billion in annual sales, becoming the fastest retailer in history to do so.

Rather than failing, Apple Stores radically shifted the Mac away from being presented as an oddball, expensive PC. Instead, they focused on its unique strengths in photography, music and video. They highlighted the Mac’s ease of use, and enabled Apple to introduce new services ranging from .Mac to today’s iCloud.

Beyond the Mac, its new chain of Apple Stores gave the company an exclusive place to introduce and demonstrate years of new iPods for buyers to experience hands on. By 2007, Apple Stores were in major cities across the globe. The success of the stores helped Apple build an international presence, reinforcing the perception of Apple as a global brand. Its retail presence also became a key tool in launching other new product categories, notably iPhone and iPad.

Apple Stores also gave the company a way to expand beyond computing devices into wearables like Apple Watch, AirPods, and Vision Pro, enabling buyers to try the products on, select from an array of accessories, and experience how they integrate with the rest of Apple’s ecosystem.

Apple Retail also provided a way to launch new technology features such as Retina Display, Augmented Reality, Spatial Audio and of course, its newest deployment of Spatial Computing.

Union Square Apple Store, San Francisco

Union Square Apple Store, San Francisco

By often serving as the first places to showcase its new releases, Apple Stores help build anticipation and create a buzz around new product launches. The stores themselves have historically also served as a form of advertising, attracting large crowds and media attention.

Major new flagship Apple Store locations have helped to define and anchor shopping districts— like San Francisco’s Union Square, Berlin’s Rosenthaler Strasse and Kurfrstendamm, or Paris’ Champs-lysees and Opera. Others serve as dramatic city landmarks— like New York’s landmark Fifth Avenue cube or its Grand Central location, or Chicago’s Michigan Avenue, Causeway Bay in Hong Kong, Orchard Road in Singapore, and Piazza Liberty in Milan.

Others anchor dramatic shopping centers such as Dubai Mall or Bangkok’s glitzy new IconSiam mall, which I profiled after a visit last year.

IconSiam Apple Store, Bangkok

IconSiam Apple Store, Bangkok

In that article, I wrote that IconSiam “features a high end flagship Apple Store, with high ceilings and glass walls that open out over a large park-like platform with views looking out over the river and across the city,” adding that, “The enormous amount of effort, resources, and attention to design that Apple has invested into its retail stores like this one not only makes them spectacular venues for launching new products, but also reflects the aura of Apple’s products and how much effort went into them.”

If you want to read more about Apple Retail, there are an array of books on the subject, including:

“The Apple Store: The Real Story of Life Inside the World’s Most Valuable Retail Business” by Carmen Simon

“Apple Inc. and the World of Retail: How Apple Reinvented the Retail Industry” by Kevin Marquardt

“Think Like Apple: 7 Principles for Building an Inspired and Enduring Brand” by Zoe L. Plowman

“The Genius of Apple Retail” by Gary Hoover

But next Monday, let’s take a look at a third major facet of iconic innovation from Apple created over the past 25 years, and what impact it had.